El número áureo (también llamado número de oro, razón extrema y media, razón áurea, razón dorada, media áurea, proporción áurea y divina proporción) es un número irracional, representado por la letra griega φ (phi) (en minúscula) o Φ (Phi) (en mayúscula) en honor al escultor griego Fidias.

Durante más de 2,400 años el ser humano ha tenido especial fascinación por este número. De acuerdo con Mario Livio, un astrofísico israelí:

Algunas de las mentes matemáticas más grandes de todos los tiempos, desde Pitágoras y Euclides en la antigua Grecia, pasando por el matemático medieval italiano Leonardo de Pisa y el astrónomo renacentista Johannes Kepler, hasta figuras científicas actuales como el físico de Oxford Roger Penrose, han pasado horas interminables estudiando sobre esta simple relación y sus propiedades. Pero la fascinación por la Proporción Dorada no se limita solo a los matemáticos. Biólogos, artistas, músicos, historiadores, arquitectos, psicólogos e incluso místicos han meditado y debatido la base de su ubicuidad y atractivo. De hecho, es probable que sea justo decir que la Proporción Dorada ha inspirado a pensadores de todas las disciplinas como ningún otro número en la historia de las matemáticas.

Wikipedia.

AEn la Grecia Antigua los matemáticos estudiaban la proporción áurea dada su profusa aparición en geometría;

La división de una línea en «proporción extrema y media» (la sección dorada) es importante en la geometría de los pentagramas y pentágonos regulares. Se supone que sobre el siglo V a.C. el matemático Hippasus descubrió que la proporción áurea no era un número entero ni una fracción para sorpresa de los Pitagóricos. En su obra Los Elementos, Euclides (c. 300 aC) nos propone varias pruebas de uso de la proporción áurea y la primera definición de la misma de la que tenemos constancia:

Un segmento se dice que está dividido en su razón extrema y media cuando el total del segmento es a la parte mayor como la parte mayor a la menor.

Euclides (Los Elementos: Libro IV, Definición 3)

La proporción áurea fue objeto de estudio también durante el siguiente milenio. Abu Kamil (c. 850–930) lo utilizaba en sus cálculos geométricos para pentágonos y decágonos. Sus estudios influyeron en ed that of Fibonacci (Leonardo de Pisa) (c. 1170–1250), quien usó esta ratio en sus problemas de geometría aunque nunca estableció una conexión con la serie de números que lleva su nombre, cosa que se haría posteriormente. Luca Pacioli usó esta ratio para poner título a una de sus obras Divina proportione (1509) donde exploraba sus propiedades incluyendo su apariencia en algunos de los Sólidos Platónicos ( poliedros convexos tal que todas sus caras son polígonos regulares iguales entre sí,). Leonardo da Vinci, quien ilustró el libro antes mencionado, llamó a esta ratio sectio aurea (‘sección áurea’). En el siglo XVI matemáticos como Rafael Bombelli resolvieron algunos problemas de geometría utilizando esta ratio. Fué Michael Maestlin (s. XVI) el primero en especificar una aproximación decimal al número áureo.

El matemático Simon Jacob (d. 1564) descrubrió que números consecutivos de la serie de Fibonacci convergen al número áureo. Este hecho fue «redescubierto» por Johannes Kepler en 1608. La primera aproximación conocida del la proporción áurea fue una fracción decimal establecida en «0.6180340», por Michael Maestlin en 1597 en la University of Tübingen en una carta que envió a Kepler, quien fue estudiante suyo. Ese mismo año Kepler respondió a Maestlin con el Triángulo de Kepler que combina el número áureo con el Teorema de Pitágoras:

Geometry has two great treasures: one is the Theorem of Pythagoras, and the other the division of a line into extreme and mean ratio; the first we may compare to a measure of gold, the second we may name a precious jewel.

Kepler

Martin Ohm usó por primera vez el término german goldener Schnitt (‘sección áurea’) para describir esta ratio en 1835. James Sully usó el término equivalente en inglés en 1875.

Fue el matemático Mark Barr quien propuso el uso de la primera letra del escultor de la Grecia Antigua Phidias, phi, como símbolo del número áureo. Normalmente se usa en minúscula (φ o φ) y se reserva la mayúscula para designar el recíproco del número áureo: 1/φ. Empezó a usar esta letra para designarlo allá por el 1910. También se ha representado con la letra griega tau (τ), la primera letra de la palabra τομή (‘sección’).

En 1974, Roger Penrose descubrío que el patrón de Penrose tiling, (Una teselación o suelo de baldosas no periódica generada por un conjunto aperiódico de baldosas prototipo nombradas en honor a Roger Penrose, quien investigó esos conjuntos en la década de los 70) está relacionada con el número áure …. to the golden ratio both in the ratio of areas of its two rhombic tiles and in their relative frequency within the pattern. This led to Dan Shechtman‘s early 1980s discovery of quasicrystals, some of which exhibit icosahedral symmetry.[39][40]

Applications and observations

Architecture

Further information: Mathematics and architecture

A 2004 geometrical analysis of earlier research into the Great Mosque of Kairouan reveals a consistent application of the golden ratio throughout the design, according to Boussora and Mazouz. They found ratios close to the golden ratio in the overall proportion of the plan and in the dimensioning of the prayer space, the court, and the minaret. The authors note, however, that the areas where ratios close to the golden ratio were found are not part of the original construction, and theorize that these elements were added in a reconstruction.

The Swiss architect Le Corbusier, famous for his contributions to the modern international style, centered his design philosophy on systems of harmony and proportion. Le Corbusier’s faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden ratio and the Fibonacci series, which he described as «rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section by children, old men, savages and the learned.»

Le Corbusier explicitly used the golden ratio in his Modulor system for the scale of architectural proportion. He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci’s «Vitruvian Man«, the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture. In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit. He took suggestion of the golden ratio in human proportions to an extreme: he sectioned his model human body’s height at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then subdivided those sections in golden ratio at the knees and throat; he used these golden ratio proportions in the Modulor system. Le Corbusier’s 1927 Villa Stein in Garches exemplified the Modulor system’s application. The villa’s rectangular ground plan, elevation, and inner structure closely approximate golden rectangles.[44]

Another Swiss architect, Mario Botta, bases many of his designs on geometric figures. Several private houses he designed in Switzerland are composed of squares and circles, cubes and cylinders. In a house he designed in Origlio, the golden ratio is the proportion between the central section and the side sections of the house.[45]

In a recent book, author Jason Elliot speculated that the golden ratio was used by the designers of the Naqsh-e Jahan Square and the adjacent Lotfollah mosque.

From measurements of 15 temples, 18 monumental tombs, 8 sarcophagi, and 58 grave stelae from the fifth century BC to the second century AD, one researcher has concluded that the golden ratio was totally absent from Greek architecture of the classical fifth century BC, and almost absent during the following six centuries.

Art

See also: Mathematics and art and History of aesthetics before the 20th century

Divina proportione (Divine proportion), a three-volume work by Luca Pacioli, was published in 1509. Pacioli, a Franciscan friar, was known mostly as a mathematician, but he was also trained and keenly interested in art. Divina proportione explored the mathematics of the golden ratio. Though it is often said that Pacioli advocated the golden ratio’s application to yield pleasing, harmonious proportions, Livio points out that the interpretation has been traced to an error in 1799, and that Pacioli actually advocated the Vitruvian system of rational proportions. Pacioli also saw Catholic religious significance in the ratio, which led to his work’s title.The drawing of a man’s body in a pentagram suggests relationships to the golden ratio.

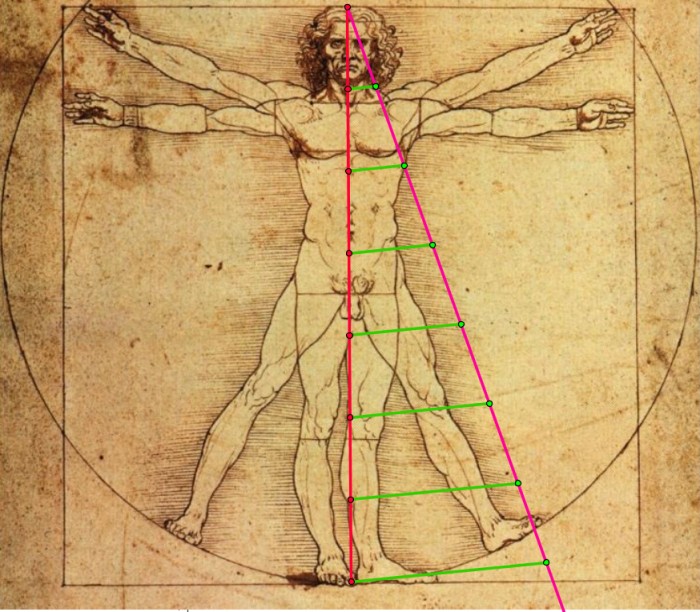

Leonardo da Vinci‘s illustrations of polyhedra in Divina proportione have led some to speculate that he incorporated the golden ratio in his paintings. But the suggestion that his Mona Lisa, for example, employs golden ratio proportions, is not supported by Leonardo’s own writings. Similarly, although the Vitruvian Man is often shown in connection with the golden ratio, the proportions of the figure do not actually match it, and the text only mentions whole number ratios.

The 16th-century philosopher Heinrich Agrippa drew a man over a pentagram inside a circle, implying a more direct relationship to the golden ratio.

Salvador Dalí, influenced by the works of Matila Ghyka, explicitly used the golden ratio in his masterpiece, The Sacrament of the Last Supper. The dimensions of the canvas are a golden rectangle. A huge dodecahedron, in perspective so that edges appear in golden ratio to one another, is suspended above and behind Jesus and dominates the composition.

A statistical study on 565 works of art of different great painters, performed in 1999, found that these artists had not used the golden ratio in the size of their canvases. The study concluded that the average ratio of the two sides of the paintings studied is 1.34, with averages for individual artists ranging from 1.04 (Goya) to 1.46 (Bellini).[55] On the other hand, Pablo Tosto listed over 350 works by well-known artists, including more than 100 which have canvasses with golden rectangle and root-5 proportions, and others with proportions like root-2, 3, 4, and 6.

Book design

Depiction of the proportions in a medieval manuscript. According to Jan Tschichold: «Page proportion 2:3. Margin proportions 1:1:2:3. Text area proportioned in the Golden Section.»[57]Main article: Canons of page construction

According to Jan Tschichold,

There was a time when deviations from the truly beautiful page proportions 2:3, 1:√3, and the Golden Section were rare. Many books produced between 1550 and 1770 show these proportions exactly, to within half a millimeter.

Design

Some sources claim that the golden ratio is commonly used in everyday design, for example in the shapes of postcards, playing cards, posters, wide-screen televisions, photographs, light switch plates and cars.

Music

Ernő Lendvai analyzes Béla Bartók‘s works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden ratio and the acoustic scale,[64]though other music scholars reject that analysis. French composer Erik Satie used the golden ratio in several of his pieces, including Sonneries de la Rose+Croix. The golden ratio is also apparent in the organization of the sections in the music of Debussy‘s Reflets dans l’eau (Reflections in Water), from Images (1st series, 1905), in which «the sequence of keys is marked out by the intervals 34, 21, 13 and 8, and the main climax sits at the phi position».

The musicologist Roy Howat has observed that the formal boundaries of Debussy’s La Mer correspond exactly to the golden section.[67]Trezise finds the intrinsic evidence «remarkable», but cautions that no written or reported evidence suggests that Debussy consciously sought such proportions.

Pearl Drums positions the air vents on its Masters Premium models based on the golden ratio. The company claims that this arrangement improves bass response and has applied for a patent on this innovation.

Though Heinz Bohlen proposed the non-octave-repeating 833 cents scale based on combination tones, the tuning features relations based on the golden ratio. As a musical interval the ratio 1.618… is 833.090… cents (Play (help·info)).

Deja una respuesta